|

| |

| |

|

An Investigation into

Childhood Leukaemia in Northampton An Investigation into

Childhood Leukaemia in Northampton

Return to the Index Page

"We want to find our why our children are getting leukaemia"

|

|

|

| 5.1 |

Do five cases mean there is something nasty going on?

We have said that

childhood leukaemia is an uncommon disease and, from the above figures,

it is clear that there are more cases of childhood leukaemia in the Pembroke

Road area than one would normally expect. We have said that

childhood leukaemia is an uncommon disease and, from the above figures,

it is clear that there are more cases of childhood leukaemia in the Pembroke

Road area than one would normally expect. |

"I won't accept it as a

coincidence" 8

A parent

|

| "... the cases in Pembroke Road, although

extremely serious and distressing for the families concerned, could have

occurred by chance." 9

Director of Public Health

|

It is quite natural

that people worry that there might be something in the area that has caused

leukaemia in these children. Most people, including medical professionals,

have the gut feeling that this "can't possibly be a coincidence". Yet Northamptonshire

Health Authority have consistently maintained that this cluster could be

a chance occurrence and this view has been confirmed by all of the child

cancer experts and epidemiologists we have talked to. So why

do we say this? It is quite natural

that people worry that there might be something in the area that has caused

leukaemia in these children. Most people, including medical professionals,

have the gut feeling that this "can't possibly be a coincidence". Yet Northamptonshire

Health Authority have consistently maintained that this cluster could be

a chance occurrence and this view has been confirmed by all of the child

cancer experts and epidemiologists we have talked to. So why

do we say this? |

This section explains

why we believe that the Pembroke Road leukaemia cluster is likely to be

just be coincidence. It is very important to understand this as it

is the key to understanding why it is not yet possible for epidemiologists

and doctors to tell us what caused leukaemia in our children. This section explains

why we believe that the Pembroke Road leukaemia cluster is likely to be

just be coincidence. It is very important to understand this as it

is the key to understanding why it is not yet possible for epidemiologists

and doctors to tell us what caused leukaemia in our children. |

|

| 5.2 |

Clusters can occur by chance

Firstly, random (i.e. chance) events

cluster. Random distribution is not uniform but features clustering.

Figure 2 below shows a matrix of 100 squares containing 40 random numbers

between 0-99 drawn from random number tables, and marked as crosses on

the grid 10. Firstly, random (i.e. chance) events

cluster. Random distribution is not uniform but features clustering.

Figure 2 below shows a matrix of 100 squares containing 40 random numbers

between 0-99 drawn from random number tables, and marked as crosses on

the grid 10.

The average number of crosses

expected in each square is 0.4 but one square contains 4 crosses, that

is, 10 times the expected number and one contains three crosses.

These clusters have occurred merely by chance. The average number of crosses

expected in each square is 0.4 but one square contains 4 crosses, that

is, 10 times the expected number and one contains three crosses.

These clusters have occurred merely by chance.

This phenomenon of clustering

of chance events, without any underlying "cause" or risk factor, is seen

time and time again. Take the UK National Lottery as an example:

since it started in November 1994 to the time of writing, there have been

56 draws. Each week 7 balls (6 plus the bonus ball) are drawn from

a possible 49 balls. Thus 392 balls have been drawn to date.

On average one would expect any particular number to have come up 8 times.

However, in over a year the number 39 has only come up once while

the number 5 has come up 15 times. The risk of drawing

a 5 was 15 times the risk of drawing a 39 during this

period! However, this is does not mean that the lottery is fixed,

that there is "something nasty" going on behind the scenes, it is simply

due to chance. This phenomenon of clustering

of chance events, without any underlying "cause" or risk factor, is seen

time and time again. Take the UK National Lottery as an example:

since it started in November 1994 to the time of writing, there have been

56 draws. Each week 7 balls (6 plus the bonus ball) are drawn from

a possible 49 balls. Thus 392 balls have been drawn to date.

On average one would expect any particular number to have come up 8 times.

However, in over a year the number 39 has only come up once while

the number 5 has come up 15 times. The risk of drawing

a 5 was 15 times the risk of drawing a 39 during this

period! However, this is does not mean that the lottery is fixed,

that there is "something nasty" going on behind the scenes, it is simply

due to chance.

|

| 5.3 |

Apparent clusters can be due to artefact

We are able to understand the world

we live in because of our natural ability to distinguish patterns.

We are constantly categorising what we see in order to simplify and make

sense of what is about us. Sometimes the patterns that we see are

imposed by us rather than being an objective feature of the world.

When this happens the pattern is not real but an artefact.

There is considerable evidence that shows that many of the disease "clusters"

we see (for many diseases not just leukaemia) are due to the way we look

at the world, that is they are artefactual. We are able to understand the world

we live in because of our natural ability to distinguish patterns.

We are constantly categorising what we see in order to simplify and make

sense of what is about us. Sometimes the patterns that we see are

imposed by us rather than being an objective feature of the world.

When this happens the pattern is not real but an artefact.

There is considerable evidence that shows that many of the disease "clusters"

we see (for many diseases not just leukaemia) are due to the way we look

at the world, that is they are artefactual.

The

key problem lies in how we define what we are going to call a cluster.

We need to have boundaries that limit what we are talking about.

Boundaries are not just the lines we draw defining the area or place where

we think the cluster is; boundaries are needed to delimit everything that

defines the cluster. Criteria that need to be specified to define

what counts as a "case" for the purpose of delimiting the cluster include: The

key problem lies in how we define what we are going to call a cluster.

We need to have boundaries that limit what we are talking about.

Boundaries are not just the lines we draw defining the area or place where

we think the cluster is; boundaries are needed to delimit everything that

defines the cluster. Criteria that need to be specified to define

what counts as a "case" for the purpose of delimiting the cluster include:

-

What types of illness must a person have to count as a case?

-

What geographic area or place is the cluster in (i.e. where do we stop

and start counting people with the right illness as part of our cluster)?

-

What age must a person be to count as a case?

-

Do people with the right illness have to be born, or diagnosed, or resident

at some time prior to diagnosis, in the geographic area defining the cluster

to count as a case?

-

What time period does a person have to have become ill in to count as a

case?

and so forth ...

|

"An even more serious problem

with some surveys of leukaemia.. is a tendency to draw the boundaries after

seeing the data. It is essential to draw all boundaries (in space, time,

age group and type of disease) before conducting the survey. Otherwise

it is easy to create highly improbable incidences by choosing tight boundaries

around apparent clusters... Studies by people who are not aware of the

problem can lead to apparently frightening results." 11

The New Scientist

|

Our natural analytical attitude

means that we subtly and unconsciously shift boundaries around to

maximise the clustering effect. This can be illustrated by considering

how the Pembroke Road cluster has been defined in relation to some of the

criteria listed above. Our natural analytical attitude

means that we subtly and unconsciously shift boundaries around to

maximise the clustering effect. This can be illustrated by considering

how the Pembroke Road cluster has been defined in relation to some of the

criteria listed above. |

|

5.3.1 - What types of illness counts as a "case"?

Are we interested in any cancer

in Pembroke Road area or only leukaemia? What about lymphoma, that

is often counted in the same group as leukaemia and shares some of its

risk factors? Are we going to count all the different sorts

of leukaemia or only the one that most children get, which is known as

ALL. Some of the children in

Table 1, do not have ALL but CML

should they be considered as part of the cluster? Normally

we do not actually ask these questions because it just seems natural to

select the case definition that makes the cluster seem bigger: we

think we are just describing an objective feature of the world. In

fact we are subconsciously drawing boundaries to maximise the effect.

Thus in the Pembroke Road area we are not very interested in other childhood

cancers or adult cancers because the incidence of these is unremarkable,

however, if they had been high we would have immediately added them

to the pot! Are we interested in any cancer

in Pembroke Road area or only leukaemia? What about lymphoma, that

is often counted in the same group as leukaemia and shares some of its

risk factors? Are we going to count all the different sorts

of leukaemia or only the one that most children get, which is known as

ALL. Some of the children in

Table 1, do not have ALL but CML

should they be considered as part of the cluster? Normally

we do not actually ask these questions because it just seems natural to

select the case definition that makes the cluster seem bigger: we

think we are just describing an objective feature of the world. In

fact we are subconsciously drawing boundaries to maximise the effect.

Thus in the Pembroke Road area we are not very interested in other childhood

cancers or adult cancers because the incidence of these is unremarkable,

however, if they had been high we would have immediately added them

to the pot!

In fact Northamptonshire Health

Authority did check with the Oxford Cancer Intelligence Unit about other

cancers in both children and adults. We looked at all cancers in

the NN5 7** post-code sector for the decade 1983-1992. We did not

find more people with cancer than expected 12. In fact Northamptonshire Health

Authority did check with the Oxford Cancer Intelligence Unit about other

cancers in both children and adults. We looked at all cancers in

the NN5 7** post-code sector for the decade 1983-1992. We did not

find more people with cancer than expected 12.

|

|

5.3.2 - What areas or places constitute part of the cluster?

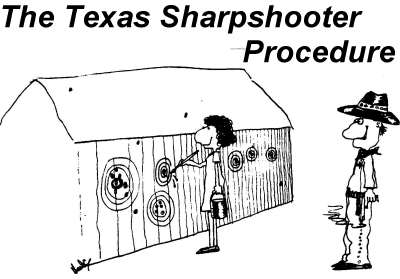

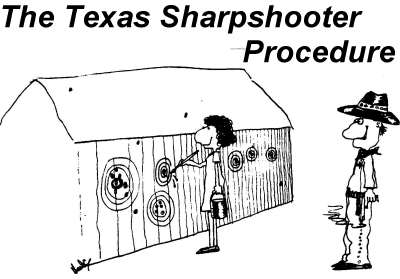

This problem of shifting boundaries

is probably best illustrated by the defining of geographical boundaries.

We have already seen that chance events cluster. Therefore, when we think

we may have a cluster we need to ask ourselves not only whether it is a

cluster but also whether it is the sort of cluster we would expect to see

occasionally because of chance clustering? It is important to look

at the statistical significance of a cluster in the context of what is

expected from the overall distribution. We do not naturally

do this. We do the opposite. It is our natural inclination

to mentally draw as tight a line around a cluster as we can. So,

for example, our leukaemia cluster is not in Northamptonshire nor

Northampton nor even the Spencer Estate but in "the Pembroke Road area",

i.e. the smallest area that can be drawn around the five cases. Note

also that it is not just Pembroke Road because this would not have

maximised the number of cases making up the cluster (3 of the children

with leukaemia are from Pembroke Road on lives in Countess Road nearby).

This natural behaviour can make it seem as if there is a cluster when there

is not one, or that there is a bigger cluster than there really is. This

phenomenon is known as The Texas Sharpshooter's Procedure 13:

the sharpshooter first fires at the side of the barn and then paints a

bulls eye around the bullet hole. This problem of shifting boundaries

is probably best illustrated by the defining of geographical boundaries.

We have already seen that chance events cluster. Therefore, when we think

we may have a cluster we need to ask ourselves not only whether it is a

cluster but also whether it is the sort of cluster we would expect to see

occasionally because of chance clustering? It is important to look

at the statistical significance of a cluster in the context of what is

expected from the overall distribution. We do not naturally

do this. We do the opposite. It is our natural inclination

to mentally draw as tight a line around a cluster as we can. So,

for example, our leukaemia cluster is not in Northamptonshire nor

Northampton nor even the Spencer Estate but in "the Pembroke Road area",

i.e. the smallest area that can be drawn around the five cases. Note

also that it is not just Pembroke Road because this would not have

maximised the number of cases making up the cluster (3 of the children

with leukaemia are from Pembroke Road on lives in Countess Road nearby).

This natural behaviour can make it seem as if there is a cluster when there

is not one, or that there is a bigger cluster than there really is. This

phenomenon is known as The Texas Sharpshooter's Procedure 13:

the sharpshooter first fires at the side of the barn and then paints a

bulls eye around the bullet hole.

If one reviews the press coverage

of the leukaemia cluster in the Pembroke Road area one can see this shifting

boundary phenomenon in action. Here are just a few examples: If one reviews the press coverage

of the leukaemia cluster in the Pembroke Road area one can see this shifting

boundary phenomenon in action. Here are just a few examples:

-

The case definition is shifted to include adults:

-

"The toll of cancer cases in Pembroke Road, Northampton has risen to

six. In a new development the Chronicle and Echo has been told of

two more victims in the street. Now two adults are known to have had the

cancer" 14 ¶

-

The case definition is shifted to include other diagnoses:

-

"The latest victims to emerge include father-of-three who was diagnosed

with lymphatic cancer - linked with leukaemia - in 1989. He died aged 50

in 1992." 12

-

The case definition is shifted to include a transient population:

-

"Mother-of-five said her brother was diagnosed with leukaemia. He had

stayed with her when she was still living at Pembroke road." 12

-

The geographic boundaries are extended from the Pembroke Road area to capture

extra cases:

-

"We can now reveal that two more leukaemia cases have been found in

nearby Kings Heath and Duston." 15

¶ NB This paragraph also shifts the place of residence of

one of the children with leukaemia.

In the light of all the above

considerations it is not surprising to learn that there are frequent reports

of clusters of childhood leukaemia 16. In the light of all the above

considerations it is not surprising to learn that there are frequent reports

of clusters of childhood leukaemia 16.

|

| 5.4 |

So much for theory but what about practice?

5.4.1 - Methodological research

If our minds naturally generate

artefactual clusters by unconsciously shifting all the boundaries until

a cluster seems obvious and real, can we distinguish real from artefactual

clusters? If our minds naturally generate

artefactual clusters by unconsciously shifting all the boundaries until

a cluster seems obvious and real, can we distinguish real from artefactual

clusters?

We have seen that problems with

disease cluster come from identifying the cluster while unconsciously defining

its boundaries. To get round this what investigators have to do is

to define the boundaries first (so that they cannot be manipulated sub-consciously)

and then proceed to find out if there is a cluster based on a firm case

definition and, if there is, how likely it is to have occurred by chance

- only if the Texas sharpshooter draws a bulls eye on the barn before he

shoots can we really know whether he is a sharpshooter or not! We have seen that problems with

disease cluster come from identifying the cluster while unconsciously defining

its boundaries. To get round this what investigators have to do is

to define the boundaries first (so that they cannot be manipulated sub-consciously)

and then proceed to find out if there is a cluster based on a firm case

definition and, if there is, how likely it is to have occurred by chance

- only if the Texas sharpshooter draws a bulls eye on the barn before he

shoots can we really know whether he is a sharpshooter or not!

5.4.2 - Have leukaemia clusters been looked for in this way, starting first

with a clear case definition?

Yes. Yes.

One of the most comprehensive

investigations into childhood leukaemia clusters was undertaken using data

from the Childhood Cancer Research Group Register 5.

A very large set of anonymised data, relating to over 9,000 case of childhood

leukaemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, was made available to a number of different

research groups for independent analysis. The results of the different

analyses were all published together. These showed that there was some

general evidence of a moderate degree of clustering of childhood leukaemia

across the country 17. However

the study did not attempt to determine the causes. One of the most comprehensive

investigations into childhood leukaemia clusters was undertaken using data

from the Childhood Cancer Research Group Register 5.

A very large set of anonymised data, relating to over 9,000 case of childhood

leukaemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, was made available to a number of different

research groups for independent analysis. The results of the different

analyses were all published together. These showed that there was some

general evidence of a moderate degree of clustering of childhood leukaemia

across the country 17. However

the study did not attempt to determine the causes.

Another study 18

that attempted to clarify the significance of space-time clusters of leukaemia

in children examined the incidence of cancer during childhood (0-14 years)

in Los Angeles county over a five year period. Did this reveal statistically

significant clustering of childhood leukaemia? No. Space-time

clusters of childhood leukaemia were looked for within each of 31 regions

of the county. These geographic areas were defined in advance

of examining the cancer cases. One cluster of 7 cases of leukaemia

was found in one of the regions which, had it been considered in isolation,

would have been statistically significant (that is, appear to be unlikely

to have been a chance occurrence) but when considered statistically in

relation to the overall distribution of cases was simply what one might

have expected because chance events tend to cluster. What is

really interesting about this study is that the authors then looked at

the map and deliberately drew tight boundaries around a few cases next

door to each other to "create" leukaemia clusters (like the Texas sharpshooter

drawing his bulls eye after shooting). When they did this they managed

to create 9 leukaemia clusters where the rates (and the statistical significance)

of childhood leukaemia were as high or higher than in two of the most famous

post hoc leukaemia clusters. Another study 18

that attempted to clarify the significance of space-time clusters of leukaemia

in children examined the incidence of cancer during childhood (0-14 years)

in Los Angeles county over a five year period. Did this reveal statistically

significant clustering of childhood leukaemia? No. Space-time

clusters of childhood leukaemia were looked for within each of 31 regions

of the county. These geographic areas were defined in advance

of examining the cancer cases. One cluster of 7 cases of leukaemia

was found in one of the regions which, had it been considered in isolation,

would have been statistically significant (that is, appear to be unlikely

to have been a chance occurrence) but when considered statistically in

relation to the overall distribution of cases was simply what one might

have expected because chance events tend to cluster. What is

really interesting about this study is that the authors then looked at

the map and deliberately drew tight boundaries around a few cases next

door to each other to "create" leukaemia clusters (like the Texas sharpshooter

drawing his bulls eye after shooting). When they did this they managed

to create 9 leukaemia clusters where the rates (and the statistical significance)

of childhood leukaemia were as high or higher than in two of the most famous

post hoc leukaemia clusters.

Thus not only are there good

theoretical reasons why what appears to be an obvious and statistically

significant cluster probably is not, this evidence from methodological

research is a practical demonstration that striking clusters can

simply be due to artefact. Evidence like this suggests that we must

be very cautious before concluding that clusters are not due to chance:

there does not have to be a hidden cause for us to see a clear cluster

that "couldn't possibly be a coincidence". Thus not only are there good

theoretical reasons why what appears to be an obvious and statistically

significant cluster probably is not, this evidence from methodological

research is a practical demonstration that striking clusters can

simply be due to artefact. Evidence like this suggests that we must

be very cautious before concluding that clusters are not due to chance:

there does not have to be a hidden cause for us to see a clear cluster

that "couldn't possibly be a coincidence".

|

| 5.5 |

"Is there a link?"

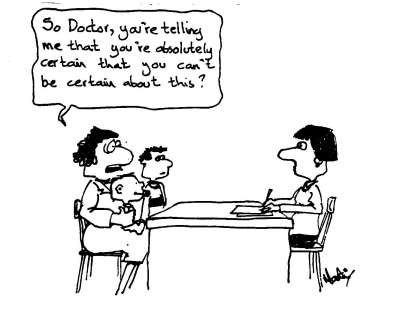

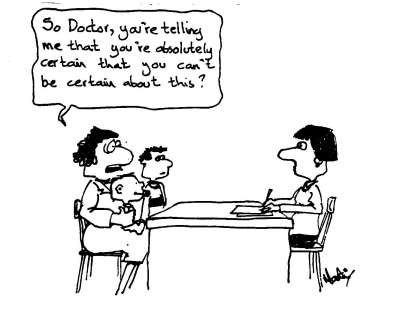

The fact that apparently

statistically significant individual disease clusters can be due to chance

or artefact is quite difficult to grasp at first as it flies in the face

of our "common sense" and intuition. This situation is not helped

when the Health Authority say things like "the cluster is consistent with

being a chance occurrence" and will not say "the cluster is just a chance

occurrence" or that the cases are "probably just a coincidence" but will

not categorically rule out the possibility of their having some common

underlying cause. The fact that apparently

statistically significant individual disease clusters can be due to chance

or artefact is quite difficult to grasp at first as it flies in the face

of our "common sense" and intuition. This situation is not helped

when the Health Authority say things like "the cluster is consistent with

being a chance occurrence" and will not say "the cluster is just a chance

occurrence" or that the cases are "probably just a coincidence" but will

not categorically rule out the possibility of their having some common

underlying cause. |

"I want the Health Authority to investigate

if there is any link between the cases"

A parent

|

| "Yes, I can understand

why a cluster of this sort is probably just due to chance but surely one

can still look at these cases and check to see if they have anything in

common that might have caused them" 19 |

This

often gets a response along the lines that "yes, it may be consistent with

being a chance occurrence but is it a chance occurrence or is there a link

between the cases?" This

often gets a response along the lines that "yes, it may be consistent with

being a chance occurrence but is it a chance occurrence or is there a link

between the cases?"

This is a very sensible question.

For example, if someone tossed a coin five times in a row and it came up

heads every time, this is consistent with being a chance occurrence (five

identical consecutive tosses will happen with a chance of about 1 in 16),

but you might still want to examine the coin to see whether it was a two-headed

coin or not! This is a very sensible question.

For example, if someone tossed a coin five times in a row and it came up

heads every time, this is consistent with being a chance occurrence (five

identical consecutive tosses will happen with a chance of about 1 in 16),

but you might still want to examine the coin to see whether it was a two-headed

coin or not!

It is quite natural that people

wonder whether the Health Authority ought to do a special investigation

into the Pembroke Road cluster to see whether that is due to chance or

not (indeed there have been numerous demands from the press and

the public that we do just that). It is quite natural that people

wonder whether the Health Authority ought to do a special investigation

into the Pembroke Road cluster to see whether that is due to chance or

not (indeed there have been numerous demands from the press and

the public that we do just that).

|

5.5.1 - Could a local investigation tell us if the cases are linked?

No, unfortunately, a special epidemiological

study would not answer this question. No, unfortunately, a special epidemiological

study would not answer this question.

Why not?

There are three main reasons why

such a study would not tell us whether the cases are linked or what caused

them. There are three main reasons why

such a study would not tell us whether the cases are linked or what caused

them.

Firstly, part of the problem

lies in what has already been talked about, the fact that the cluster could

be due to chance, as the Cancer Research Campaign point out: Firstly, part of the problem

lies in what has already been talked about, the fact that the cluster could

be due to chance, as the Cancer Research Campaign point out:

| "Clusters of childhood leukaemia have been reported but their investigation

is problematic since most of the clusters are statistically likely to be

due to chance." 20 |

Secondly, we do not know what

causes leukaemia. If we get more than one case of meningitis in Northamptonshire,

even if there are only two cases, the Health Authority immediately investigates

the cases to see if they have any common link, in case they might be part

of an outbreak, i.e. have a common cause. One of the differences

between this and leukaemia is we know what causes meningitis:

we know what to look for; there are laboratory tests that can confirm

whether two patients have got the same infection or not; there are

appropriate preventive measures that can be instituted. Another difference

between this sort of individual disease cluster and leukaemia is that they

occur much closer together in time making the identification of common

links much easier (as happens also in outbreaks of food poisoning).

Cancers have a long period of latency, that is to say, it can be

a long time between the events that cause a cancer and the appearance of

the disease itself, making it very difficult to establish common links. Secondly, we do not know what

causes leukaemia. If we get more than one case of meningitis in Northamptonshire,

even if there are only two cases, the Health Authority immediately investigates

the cases to see if they have any common link, in case they might be part

of an outbreak, i.e. have a common cause. One of the differences

between this and leukaemia is we know what causes meningitis:

we know what to look for; there are laboratory tests that can confirm

whether two patients have got the same infection or not; there are

appropriate preventive measures that can be instituted. Another difference

between this sort of individual disease cluster and leukaemia is that they

occur much closer together in time making the identification of common

links much easier (as happens also in outbreaks of food poisoning).

Cancers have a long period of latency, that is to say, it can be

a long time between the events that cause a cancer and the appearance of

the disease itself, making it very difficult to establish common links.

If we do a special study into

the Pembroke Road area we know we will find connections between the families,

such as If we do a special study into

the Pembroke Road area we know we will find connections between the families,

such as

-

the children may have been born at the same hospital

-

the families may use the same shops and buses

-

the children will play on the same playgrounds and breath the same air

but this does not help us distinguish whether the cases are connected or

a coincidence. Only if there was something highly unusual

that was common to the children with leukaemia would there be any chance

of establishing a link.

Thirdly, we have no clear hypothesis

about what might have caused these cases of leukaemia. Thirdly, we have no clear hypothesis

about what might have caused these cases of leukaemia.

A few of the hypotheses that

have been mentioned about what might have caused children in the Spencer

Estate to get leukaemia: A few of the hypotheses that

have been mentioned about what might have caused children in the Spencer

Estate to get leukaemia:

-

a spillage of nuclear fuel

-

a spillage of aviation fuel

-

weed killers or pesticides used on the railway line

-

storage of petrol tankers or petro-chemical contaminants from the railways

-

contamination by chemical aerosol from the nearby cleaning of chemical

drums

-

renewal of pipe linings from the water distribution system

-

infections

-

living near a fire hydrant

-

population mixing

-

electric or magnetic fields

-

living near the site of a tannery

-

radon gas

|

The initial suggestion, that there

had been an accident involving radioactivity on the railway, was found

not to be true. Since then there have been a great number of further

hypotheses advanced (see box above). With the lack of a clear primary

hypothesis, a study would have to be very large to be able to distinguish

between different possibilities. As one epidemiologist from the Imperial

Cancer Research Fund, Cancer Epidemiology Unit in Oxford has commented: The initial suggestion, that there

had been an accident involving radioactivity on the railway, was found

not to be true. Since then there have been a great number of further

hypotheses advanced (see box above). With the lack of a clear primary

hypothesis, a study would have to be very large to be able to distinguish

between different possibilities. As one epidemiologist from the Imperial

Cancer Research Fund, Cancer Epidemiology Unit in Oxford has commented:

| " unless a specific hypothesis is defined in advance, the relevance

of a single geographic cluster of disease can rarely be interpreted. The

statistical power of such investigations is usually low and only

marked increases in risk can be detected. Investigations of specific hypotheses

about defined sources of environmental contamination are more likely to

result in conclusive findings than are in-depth studies of individual clusters."

21 |

The Health Authority reached the

conclusion in 1993 that a special epidemiological study could not help

us find any answers and we consulted national leukaemia and cancer experts

and epidemiologists who confirmed this conclusion. We know that local

residents sought and received independent confirmation of this from Professor

Cartwright, a Professor of Cancer Epidemiology at the Leukaemia Research

Fund back in 1993: The Health Authority reached the

conclusion in 1993 that a special epidemiological study could not help

us find any answers and we consulted national leukaemia and cancer experts

and epidemiologists who confirmed this conclusion. We know that local

residents sought and received independent confirmation of this from Professor

Cartwright, a Professor of Cancer Epidemiology at the Leukaemia Research

Fund back in 1993:

| "At the present time it is not possible to distinguish random from

the non-random and this is one reason why most cluster investigations do

not come up with any conclusions. It would be impossible, I suspect,

in this instance to take this very much further." 22 |

Sadly, despite a great deal of effort

and time spent in discussing and explaining this to local journalists,

they have continued to demand the impossible "on behalf of the families".

We believe that they are doing the families of children with leukaemia

and the local community a disservice. It is vital that the right

sort of studies are undertaken to address this very serious problem - futile

investigations distract from the real work that needs to be done.

Despite very many investigations into individual childhood leukaemia

clusters, none have been conclusive. At an International Symposium

on Leukaemia Clustering held in Canada the Vice President of the Epidemiology

and Statistics Department of the American Cancer Society admitted that

at that time he did not know of any investigation of an individual

leukaemia cluster that had concluded it was due to anything other than

chance 23. At the same meeting it

was noted by another senior epidemiologist: Sadly, despite a great deal of effort

and time spent in discussing and explaining this to local journalists,

they have continued to demand the impossible "on behalf of the families".

We believe that they are doing the families of children with leukaemia

and the local community a disservice. It is vital that the right

sort of studies are undertaken to address this very serious problem - futile

investigations distract from the real work that needs to be done.

Despite very many investigations into individual childhood leukaemia

clusters, none have been conclusive. At an International Symposium

on Leukaemia Clustering held in Canada the Vice President of the Epidemiology

and Statistics Department of the American Cancer Society admitted that

at that time he did not know of any investigation of an individual

leukaemia cluster that had concluded it was due to anything other than

chance 23. At the same meeting it

was noted by another senior epidemiologist:

| "One take-home message for me is that other epidemiologists from

around the world seem to agree that formal investigation of clusters have

not been very productive those of us in cancer agencies have to figure

out how to communicate these problems so that we can concentrate our efforts

on what we feel would be productive work." 24 |

We hope this report contributes

to this effort. We hope this report contributes

to this effort.

One local paper in Northamptonshire

has argued that One local paper in Northamptonshire

has argued that

| "For the anxious parents of the Spencer Estate, any effort to pinpoint

the cause, whatever the chances of success, is better than none." 25 |

We disagree:

we feel that it would be irresponsible for the Health Authority to embark

on a course of action that had no chance of success and to do so as a "public

relations exercise" would just demonstrate contempt for the people we serve. We disagree:

we feel that it would be irresponsible for the Health Authority to embark

on a course of action that had no chance of success and to do so as a "public

relations exercise" would just demonstrate contempt for the people we serve. |

"I want to know whether the Health

Authority is willing to put any money into finding out the cause" 26

-a parent quoted in a local newspaper

|

Just for the record, the question

of cost in time or money played no part whatsoever in the decision of the

Health Authority not to institute a special study. The decision was

taken solely on methodological and scientific grounds. However, we do think

it is our duty as a Health Authority to use the resources we have available

in a responsible way. Fortunately appropriate scientific studies

are being done (e.g. the current UK Childhood Cancer Study on which an

estimated £6,000,000 will be spent 27). Just for the record, the question

of cost in time or money played no part whatsoever in the decision of the

Health Authority not to institute a special study. The decision was

taken solely on methodological and scientific grounds. However, we do think

it is our duty as a Health Authority to use the resources we have available

in a responsible way. Fortunately appropriate scientific studies

are being done (e.g. the current UK Childhood Cancer Study on which an

estimated £6,000,000 will be spent 27).

5.5.2 - How does the Health Authority decide when to do a special epidemiological

investigation?

How does the Health Authority decide

when to do a special epidemiological investigation and whether it would

stand a reasonable chance of succeeding? Following an international

conference to discuss the investigation of disease clusters, a checklist

of characteristics of clusters that suggest a special investigation may

have some chance of success was published. This is reproduced

in the table below. In the right hand column of the table we discuss

whether the Pembroke Road cluster has this characteristic or not.

The more characteristics a cluster has the more likely it is to be able

to produce some sort of result. How does the Health Authority decide

when to do a special epidemiological investigation and whether it would

stand a reasonable chance of succeeding? Following an international

conference to discuss the investigation of disease clusters, a checklist

of characteristics of clusters that suggest a special investigation may

have some chance of success was published. This is reproduced

in the table below. In the right hand column of the table we discuss

whether the Pembroke Road cluster has this characteristic or not.

The more characteristics a cluster has the more likely it is to be able

to produce some sort of result.

|

Checklist to identify clusters where special investigations

may have some chance of finding the cause or identifying new preventive

measures that can be taken 28

|

| Cluster Characteristic |

Is this characteristic seen in the Pembroke Road cluster? |

| There are at least 5 cases and the relative risk is very high

(20 or more). |

NO - Although we have enough cases, the relative risk is not

high enough (even with the most extreme interpretation of the data the

relative risk was only 5.6). |

| The disease is one for which a unique and detectable class of agents

has been responsible in the past, or the pathophysiological mechanism

is well understood. |

NO - we do not know the cause of leukaemia, epidemiologists

have only been able to identify a few risk factors and the overwhelming

majority of cases are not associated with these known risk factors.

NO - we do not yet have a detailed understanding of what is going

wrong in the body when it starts to produce too many blood cells. |

| This agent is persistent in the environment and can be measured there. |

N/A - this is not applicable since no such agent has yet been

identified. |

| The agent is persistent or leaves a physiological marker in the bodies

of people who have been exposed to it but which is rare in the normal population,

so that it can be used as an index of exposure. |

N/A - this is not applicable since no such agent has yet been

identified. |

| People who live in the same neighbourhood have different levels of

exposure to the possible cause so that effect of exposure can be assessed. |

NO - The routes of exposure to the

hazards that have been suggested as

possible causes of leukaemia in

Pembroke Road are such that everyone in the Pembroke Road area is likely

to have been exposed. So even if we had a biomarker of exposure or

effect for one of the suggested environmental hazards (which we do not),

everyone in the community would test positive to some extent. |

| The plausible route of exposure is such that subjects would be able

to accurately assess their own relevant exposure on a questionnaire or

it could be reconstructed from records. |

NO |

| It would be feasible to carry out a multicommunity study consisting

of several similarly exposed and some unexposed communities. |

NO - This is not feasible in Northampton, it needs to be done

on a larger scale. Fortunately this is what is being done in the UK Childhood

Cancer Study. |

| The cluster represents an as-yet-uninvestigated, endemic space cluster,

rather than a space-time cluster. This suggests a stable, persistent problem

and perhaps a persistent agent to be found in the environment. |

This was a theoretical possibility, however, on investigation we found

that there were NO previous cases of childhood leukaemia in this

area prior to the identification of the first case of this "cluster".Moreover

by tracing the history of the land in the Spencer Estate we found nothing

unusual or alarming. |

There is not one feature

of the cluster in Pembroke road that would suggest an investigation may

be able to help find the causes of the cases! There is not one feature

of the cluster in Pembroke road that would suggest an investigation may

be able to help find the causes of the cases! |

|

© Northamptonshire Health Authority, reproduced by kind permission

of Dr Amanda Burls, Sen Reg in Public Health Medicine.

|

An Investigation into

Childhood Leukaemia in Northampton

An Investigation into

Childhood Leukaemia in Northampton